I was born and brought up in Bridgend and went to both Brynteg and Bryntirion Comprehensive Schools. What we were taught of Welsh history was non-existent. The Bridgend of my youth, with vivid memories of the cattle market, indoor market, the Ship Inn and the iconic Town Hall are now sadly gone. Walking around the…… Continue reading Art, Landscape and Cymraeg

Merched Y Tip Cymreig Welsh Tip Girl

Oil on Canvas! No gold leaf but a hint of tin leaf for the oil can and buckle! Gold Leaf Supplies I have always been fascinated by the William Clayton collection of photographs of the Tredegar Tip Girls! As someone who worked in a scrapyard, driving lorries, how women across history worked in what is…… Continue reading Merched Y Tip Cymreig Welsh Tip Girl

Fforch Ponds Treorci

Wild swimming surrounded by beauty and history! Last year taking a walk through the forestry above Treorci to the Fforch ponds, little did i realise that not only was i surrounded by beautiful countryside but thousands of years of history! I couldn’t resist taking a photograph of my feet in the cold clear water overlooking…… Continue reading Fforch Ponds Treorci

Hen Dŷ Cwrdd in the pinc!

In the course of my paid work; as the Trust Manager of a small charity that takes ownership of historically important Welsh Chapels, I spend a lot of time in Welsh chapels across Wales. I do not ordinarily paint them but i was at Hen Dŷ Cwrdd ( Old Meeting House) in Trecynon, cleaning the…… Continue reading Hen Dŷ Cwrdd in the pinc!

The Geisha

This is a mixed media on board! 4ft x 2ft- Acrylic, Oils and Goldleaf! and forms a pair with the ‘Welsh Lady! Buy here! The Japanese word geisha or geiko literally translates “art person,” professional women who entertained men; singing, dancing, and playing the samisen a three stringed instrument! They were adept at flower arranging,…… Continue reading The Geisha

Llwynogod Melyn-Yellow Foxglove

Oil on canvas with Gold leaf (Sold) 2021 was a good year for the yellow foxgloves, too good an opportunity not to get the oil paints out! Digitalis grandiflora is a clump-forming perennial which is native to woods and stream banks from central Europe. These large, funnel-shaped, pale yellow flowers with brown speckles peaking from the…… Continue reading Llwynogod Melyn-Yellow Foxglove

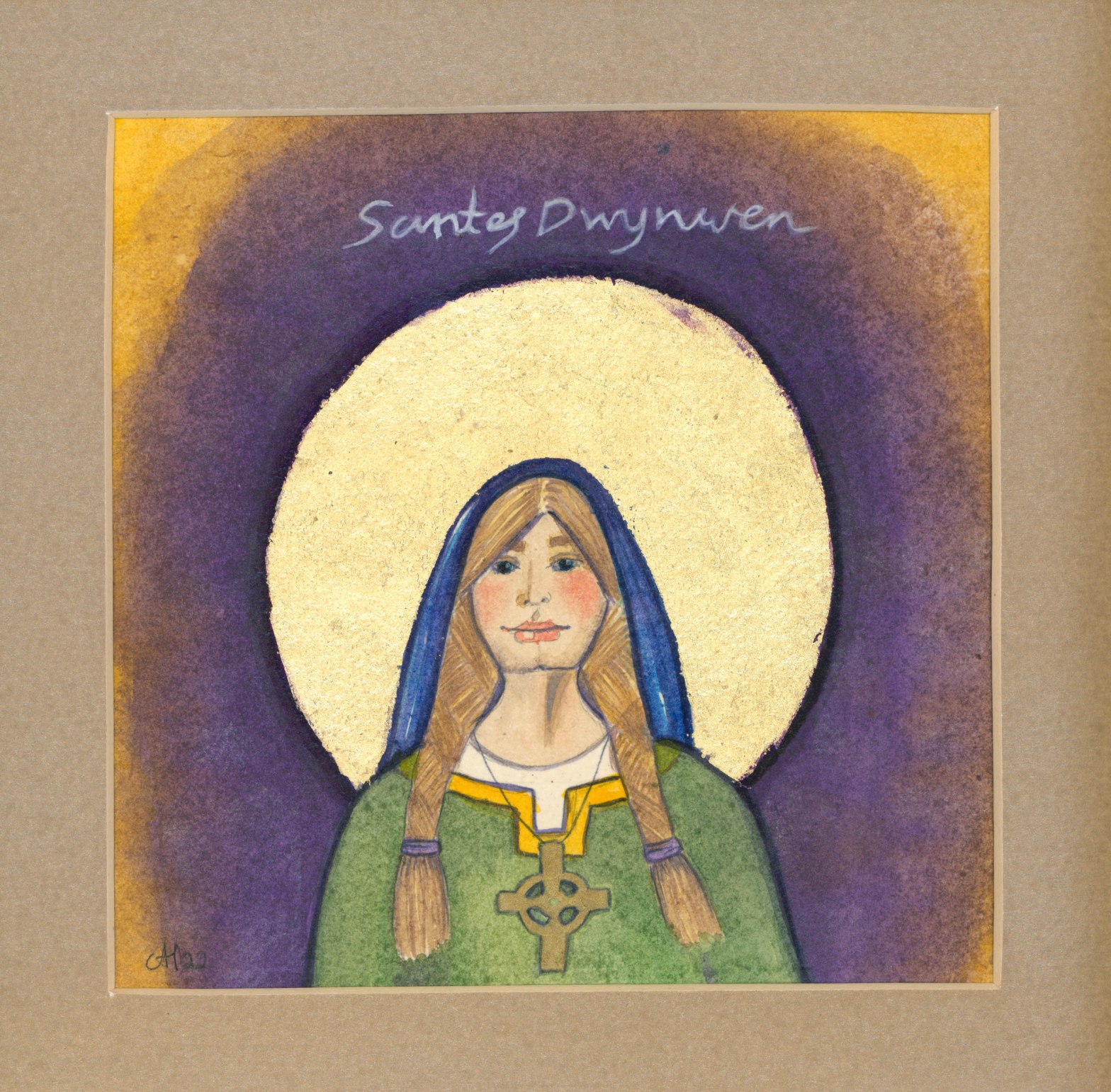

Santes Dwynwen

The story of Santes Dwynwen is a mixture of folktale and Celtic Christian stories. Santes is the female version of Sant which is Welsh for Saint. In 5th century Wales, Dwynwen was one of the prettiest daughters ofthe king of south Wales-Brychan Brycheiniog. She fell in love with Maelon Dafodrill, prince from the neighbouring land, but her father…… Continue reading Santes Dwynwen

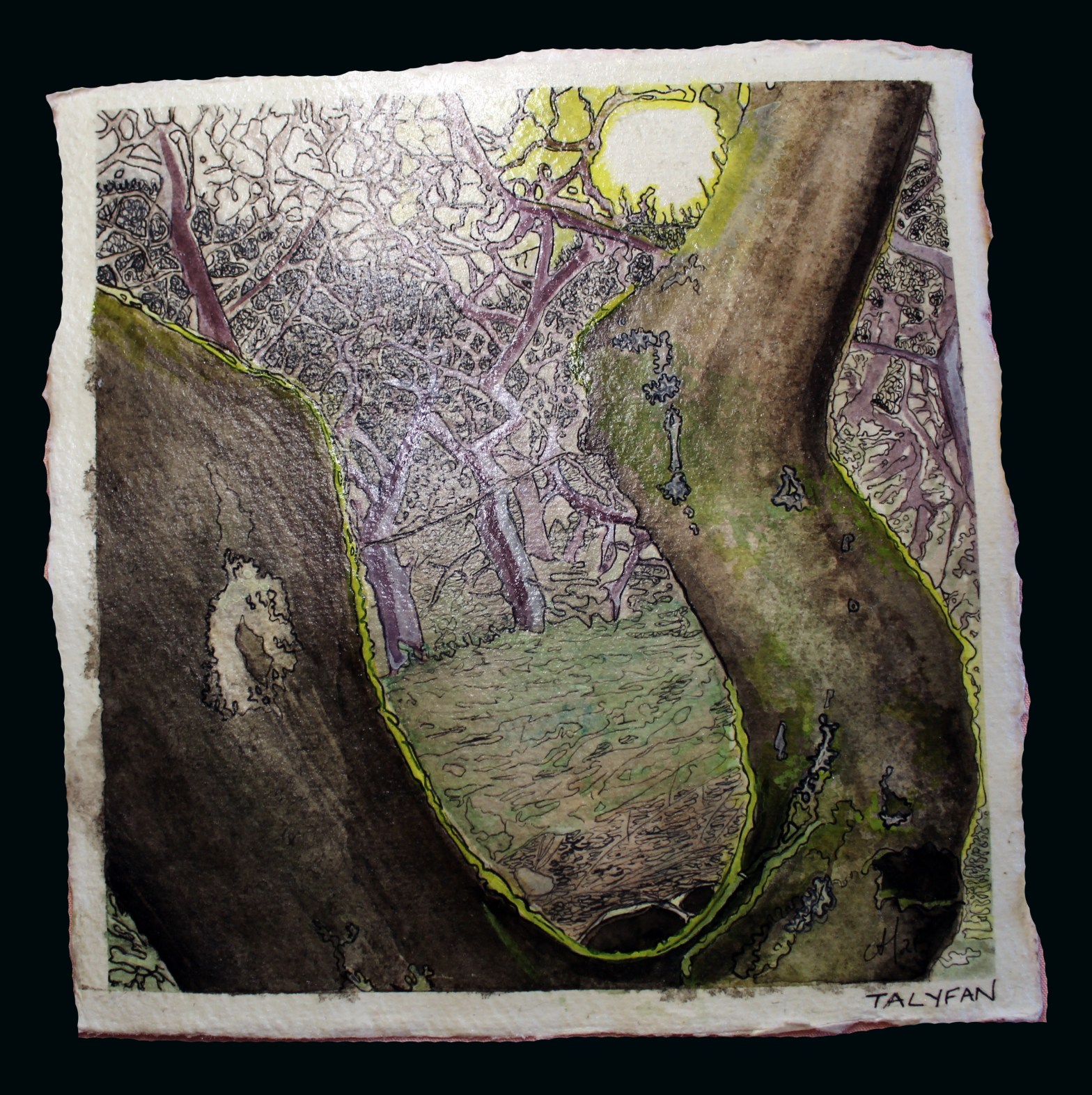

Coed Tal y Fan

Tal y Fan Trypych Craig Tal-y-fan (Tal-y-fan mountainside) and the extensive ancient woodlands on it is Coed Tal-y-Fan (Tal y Fan woods), can be found south east of Melin Ifan Ddu (Blackmill). Pre-16th century historic boundaries of Cymru were called ‘Cantrefi’, (derived from the Welsh “Cant” meaning a hundred); it was a unit of land made…… Continue reading Coed Tal y Fan

Arglwyddes Aur-Gold Lady

Sold This is a mixed media artwork: pen, watercolour and experimenting with gold leaf, inspired by the amazing Gustav Klimt (left). Now hanging on a wall in Penybont ar Ogwr! (Not the Klimt!) My love affair with shiny metal goes back to my childhood, as the daughter of a scrap merchant, copper, bronze and gold…… Continue reading Arglwyddes Aur-Gold Lady